How players themselves, coaches and policymakers can impact on football players’ health

Since early March most European football leagues were postponed, or even cancelled, due to the COVID-19 crisis. From the Top-10 leagues in Europe, the Bundesliga was the first to start again in the middle of May. Now that the coronavirus curve seems to be flattened, extensive social distance measures are in place, and wide-spread testing is available, many leagues are convinced they can safely restart. On top of that, research shows that the contamination risk during football is low1 (see frame). And so the ball also rolls again in Ukraine, Portugal, Spain and England, with the Serie A and Russian Premier League returning this weekend.

But how safe it is really? In this post I will show why the players are at enormous risks to sustain an injury, especially in the Serie A and La Liga. I will shortly explain what impact a break has on fitness, why it is difficult to mimic matches during (adapted) training sessions, and how much more demanding the match schedules are these days. In the end I will conclude with some guidelines for policymakers, coaches, and players to minimize the injury risk within their own possibilities, both for professional as well as amateur level.

Low contamination risk during football matches in professional football

Recent research by Inmotio, commissioned by the Royal Dutch Football Association (KNVB), showed that during professional football matches the risk for exposure, a condition for contamination, is relatively low. After analyzing 482 matches the conclusion was that any combination of two players rarely spent more than a couple of seconds in close proximity of each other over an entire match. Contact time between players could be further reduced by forbidding cheering together, as already mandated in the Bundesliga and other leagues. Also it could be wise to decrease the time allowed to take corner kicks, because this could limit the time spent with man-on-man marking in the penalty box just before the actual corner.

Training restrictions during the coronavirus break

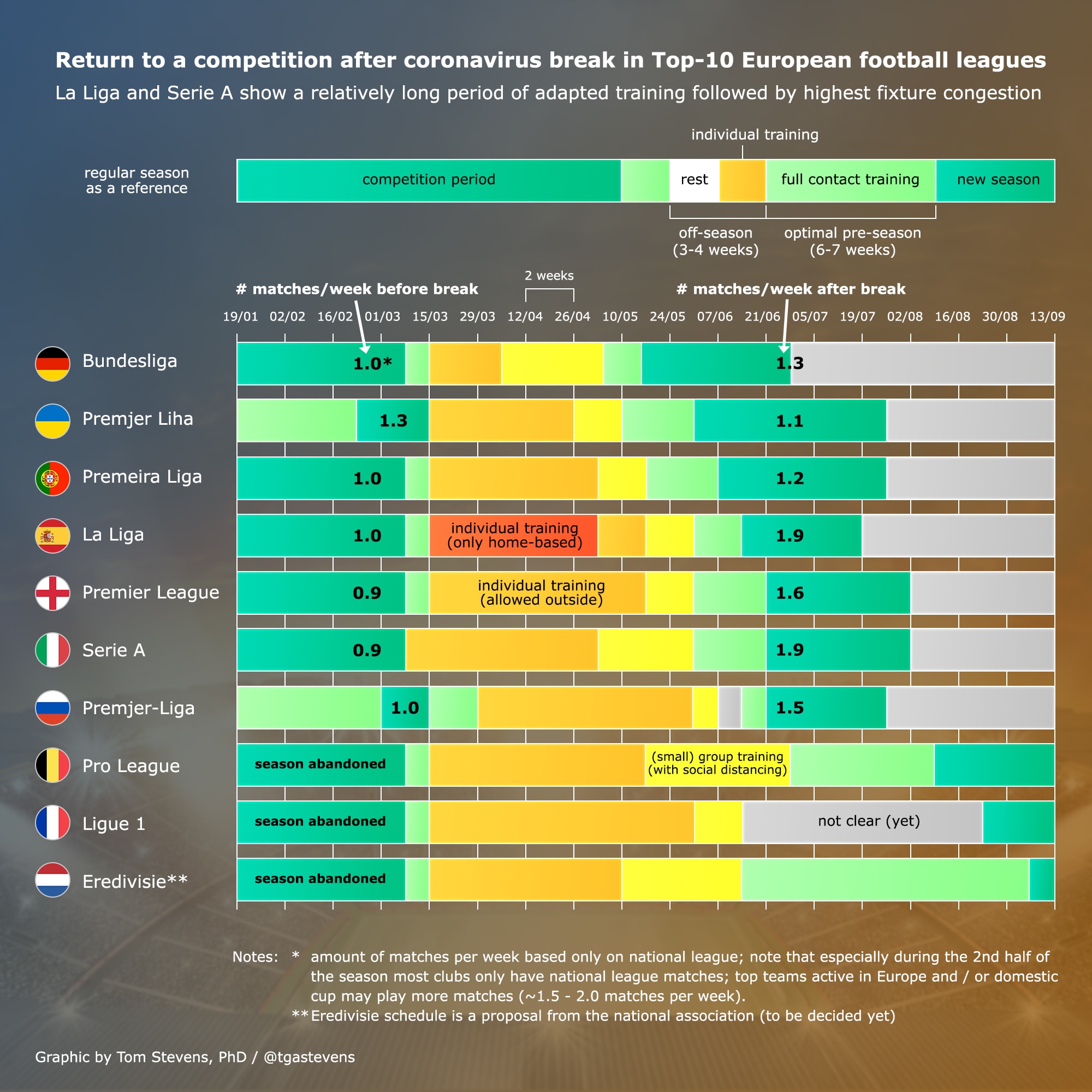

Due to the measures against COVID-19 football teams were restricted in their training possibilities (see Figure 1 below). In most countries in Europe, it was prohibited for quite some time to train in groups. At most individual training outside, close to home and with respect of social distancing, was allowed in this first phase during lockdown. Spain had even more drastic measures as people were not even allowed to go out for exercise. Since several weeks, in most countries it is possible again to train in smaller groups; however, the allowance to train in large groups and with physical contact was usually being given just before the start of the leagues.

In total, the Premier League, La Liga and the Serie A have had around eleven weeks of adapted training, followed by only 2‒3 weeks of regular ‘full contact’ training. In comparison, a regular preseason lasts usually 6‒7 weeks, and follows a period of no more than 3‒4 weeks with rest and/or reduced training on an individual basis2. The importance of a proper preseason is supported by the fact that a higher number of preseason training sessions seem to reduce injuries during the season3. However, teams in the Bundesliga, for example, had only around 10 days of full contact training before the competition restarted.

Fig. 1 — Training restrictions and fixture congestion for Top-10 European

Fig. 1 — Training restrictions and fixture congestion for Top-10 European

Impact of a break on physical fitness

Breaks can be beneficial for players in order to recover from minor or more severe injuries. Moreover, a recent study4 showed that less injuries occurred in competitions with a (short) winter break compared to competitions with no break. However, where short breaks can be beneficial to reduce injuries, longer breaks can cause physical fitness to decline rapidly5, 6. Within four weeks, a normal off-season in summer, football-specific endurance already decreases with 11%7. Also eccentric force, which could have a preventive effect for hamstring injuries8, and sport-specific power will show significant reductions9. While strength performance can be retained for 3‒4 weeks, decreases will take place after this period9, 10. The longer the break and the less training performed, the longer the preseason should be11.

Luckily, most players were still able to do some serious individual training, such as running and sprinting outdoors – some players might even have a complete home gym – in order to mitigate this decline in general endurance and strength capacity. However, some important elements of football-specific fitness definitely lacked. Admittedly, creative online training videos might have inspired athletes and trainers in trying to do so, but mimicking match-specific load and intensity load is already hard with regular training sessions, let alone in individual training.

Lower volume and intensity of training compared to match in professional football

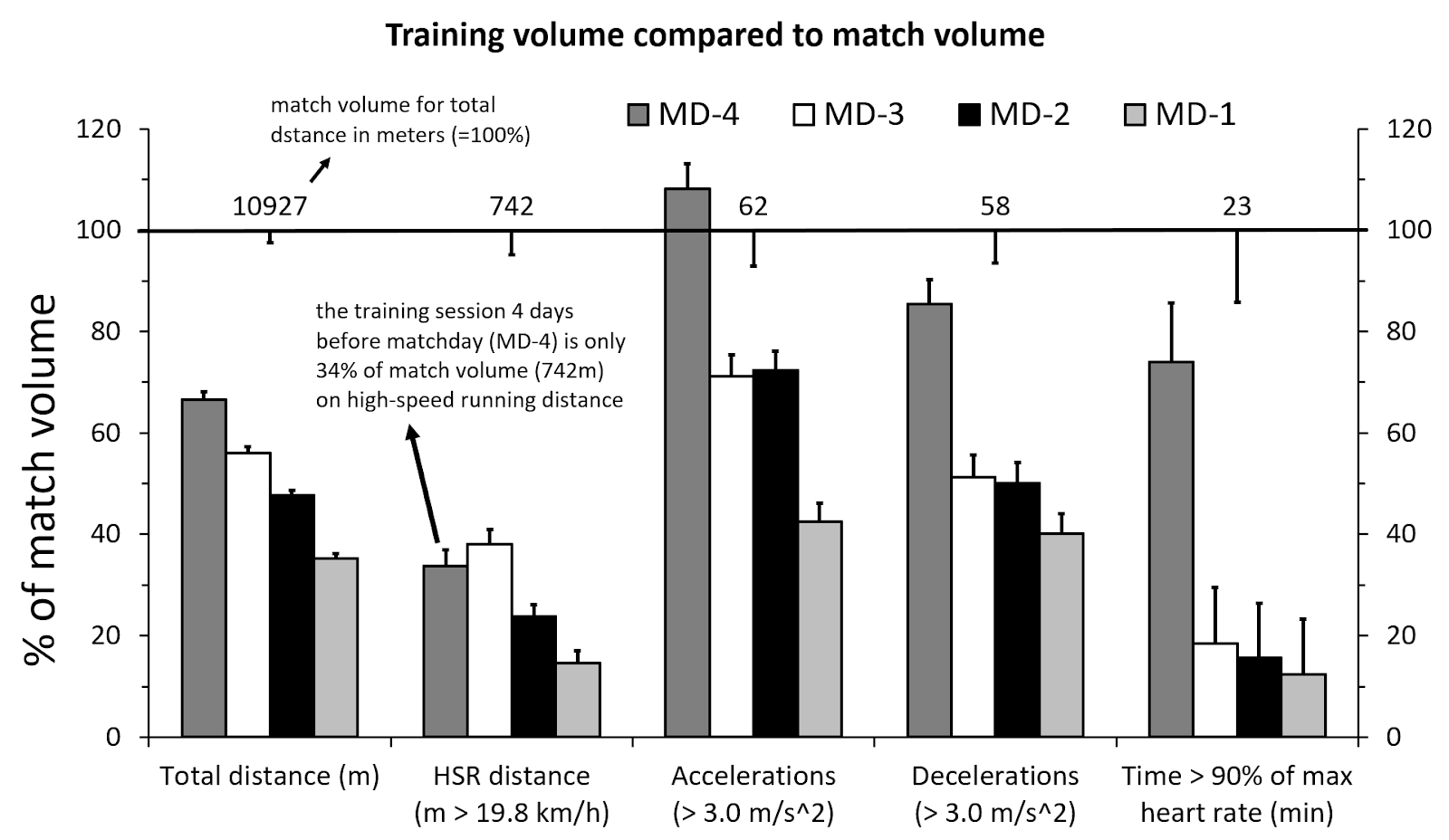

Research shows that training sessions are lower compared to (test) matches in both volume12, 13 and intensity14, especially on high speed running and sprinting (see Figure 2 + 3).

Fig. 2 — Training volume compared to match volume (mean ± 95% confidence intervals)

Fig. 2 — Training volume compared to match volume (mean ± 95% confidence intervals)

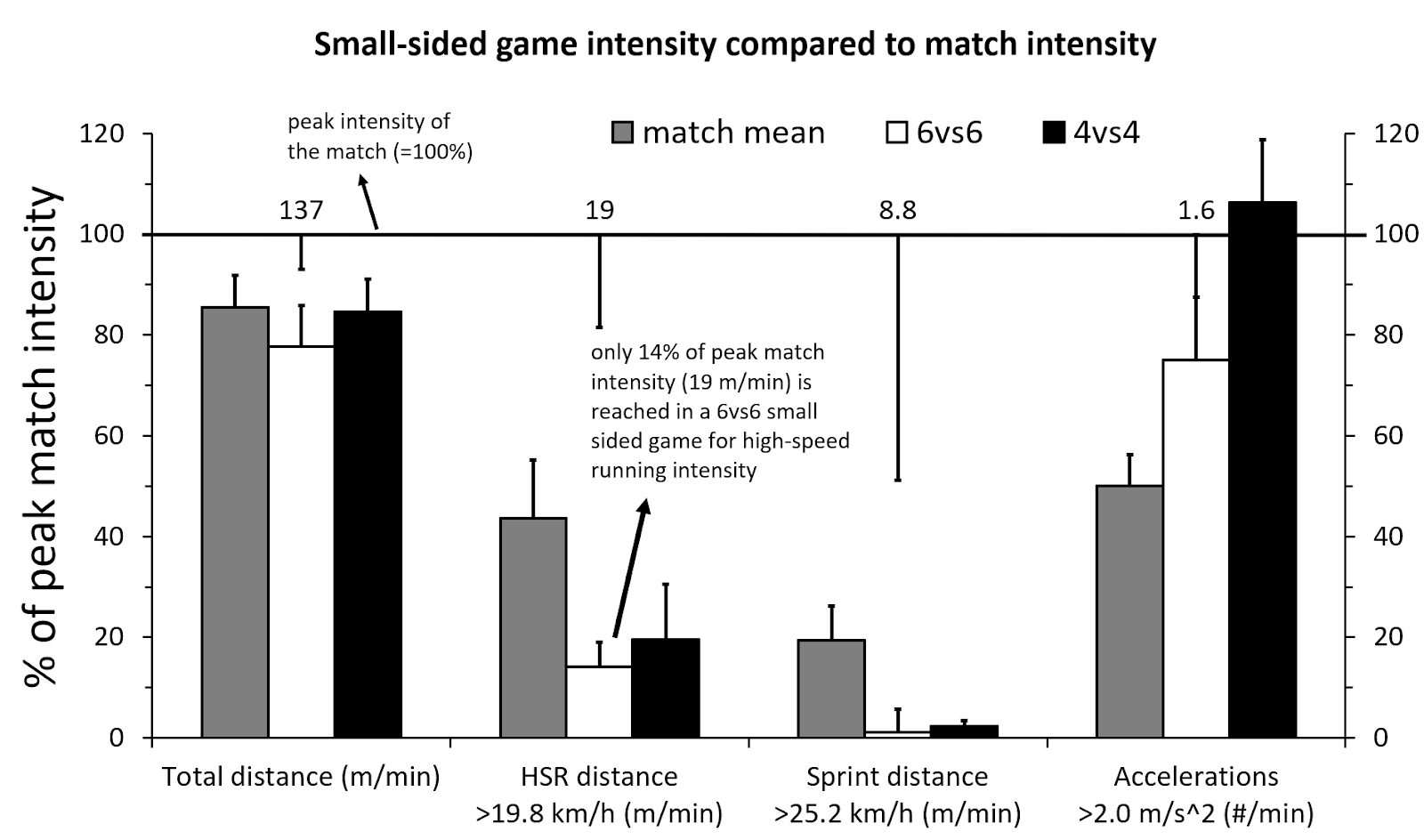

Fig. 3 — Small-sided game intensity compared to peak match intensity (mean ± 95% confidence intervals) of elite Norwegian football players (adapted with permission from Dalen et al, 2019).

Fig. 3 — Small-sided game intensity compared to peak match intensity (mean ± 95% confidence intervals) of elite Norwegian football players (adapted with permission from Dalen et al, 2019).

Admittedly, small-sided games (e.g. 4vs4 and 6vs6) and positioning games, that are often done during regular training sessions, can replicate peak intensity of matches regarding intense accelerations, but definitely not on high-speed running distance and sprint distance14. Small-sided games do not even reach the mean match intensity on these parameters (Figure 3); in other words, the worst-case scenario during matches is never trained for. That’s why usually larger sized games of at least 8vs8 or higher are needed to replicate sprint intensity in a football specific context.

Physical load of individual and even group training is therefore not comparable to match load. And even small-sided games (with contact) were not possible during the longest part of the break, so even less match specific exercise could be performed. Next to the physical load, also technical performance is affected15.

In conclusion, when at most small group training without contact is allowed, it is difficult to mimic the sport specific and/or high-speed actions. As a consequence football specific fitness and performance will reduce, therewith most likely increasing the risk for injuries16.

Fixture congestion: playing many matches in a short period of time

Another risk for injuries is the number of matches played in short periods of time. A football match is demanding and players need at least more than 3 days to fully recover17, 18 due to significant neuromuscular fatigue. Therefore, it is not surprising that the number of injuries was found to be higher when players had 4 or less days recovery compared to 6 days or more19. This was even more profound for muscle injuries20, especially for hamstring and quadriceps muscles19.

During a regular season, most teams participate only in domestic competitions, especially towards the end, and play around one match a week. Indeed, top teams may play more matches a week—actually between 1.6 and 1.9 per week for several weeks in a row—due to national cup and European obligations, but usually not directly in the beginning of the season. Moreover, to deal with these busy periods, player rotation strategies are common for national cup and even early phase European matches21.

However, at this time basically only national league matches are scheduled. And they are tightly scheduled. For example, Bayern Leverkusen played their first 4 matches after the coronavirus break within 11 days, and then had to miss their key player Havertz for some crucial matches in their hunt for Champions League qualification.

This is not an incident; in the first 6 matchdays after the coronavirus break the number of match injuries surpasses pre-coronavirus numbers by 140%22. And this figure does not include injuries sustained during training. Leverkusen manager Peter Bosz said that his players were suddenly complaining about muscle pain and that literally almost all 11 players were doubtful for the next match every week23. Also note that together with the leagues in Ukraine and Portugal the Bundesliga still has a relatively easy schedule.

Other leagues have an even more congested schedule. Aston Villa, who played their first match last Wednesday, has to play their first four matches within 10 days. That’s one match every 3.3 days to start with! Where the Premier League and Russian Premjer-Liga play on average respectively 1.5‒1.6 matches per week, real concerns should go to La Liga and Serie A. The Serie A scheduled 1.9 matches a week—a match every 3.6 days—for more than 6 weeks in a row. Even during a regular competition period, when players are optimally trained, such schedules are demanding.

Save return to competition match play – not the coronavirus, but lack of time is the biggest enemy

The FIFPRO, the global organization representing all professional football players, tries to fight against the crazy match schedules24. Coaches such as Klopp and Guardiola are on there side saying the current schedules ‘will kill’ the players and the game. However, now that the survival of clubs is at stake, in which case players are about to lose their jobs, even they are trapped within the football economic structure. DFB-boss Christian Seifert said ‘that tens of thousands of jobs’ were at stake if the Bundesliga did not start soon25. And that’s one of the main reasons why leagues rush to complete the season.

In conclusion, when safety measures are being followed around the pitch, the coronavirus is probably not the greatest threat to the health of the football players themselves. It’s the long break with reduced training, the short sport-specific preparation and the intense match schedules that will cause many injuries to occur in the weeks and months to come, especially in Spain and Italy.

Hopefully for the players involved these are not career threatening as probably the biggest predictor for new injuries are … indeed: previous injuries26. The decisions to abandon the Dutch Eredivisie, Belgium Pro League, and French Ligue 1, which were labeled as too rushed by some, might have saved some careers.

How to act now? Shared responsibility for policymakers, coaches and players

The leagues that are currently on their way will probably not adjust their schedules or rules anymore. However, some other major leagues, such as Ligue 1, the Pro League and Eredivisie, still have some time to, together with their governments, agree on a safer (return to) competition plan. The same accounts for the many amateur competitions in Europe and the rest of the world.

Assuming the coronavirus curves stay low, there are some training and match guidelines that should be made possible by policymakers and wise to follow by coaches and (amateur) players. These guidelines, based on a combination of previously referred research, expert opinions and my own choice are presented below. I hope that most of these guidelines will stay in the stakeholders minds also for the upcoming years.

Some guidelines for a safe return to competition

1. A progressive buildup of training, especially regarding high-intensity and speed training, preferably football specific

Policymakers

- Allow enough time for full contact training and test matches before competition, at least four, but preferably six weeks;

- Reduce match time (i.e. 70 minutes) in the beginning of the season and/or cup matches (especially for amateur competitions).

Coaches and other practitioners:

- Start as early as possible with football-specific training: better an extra short break during preseason than starting (too) late and pushing hard to catch up;

- Gradually increase intensity, frequency and volume of training;

- Focus on intensity of (football-specific) training, rather than total volume;

- Monitor external training load with tracking technology when possible to ensure you are doing enough, but also not too less.

Players

- Start as early as possible with football-specific training;

- Do extra injury prevention training, like core stability exercises; in doubt what to do? Ask a physio or a fitness coach;

- If you didn’t do enough last weeks or months, be honest, don’t push too hard.

- Monitoring players’ health situations and fitness levels.

2. Monitoring players’ health situations and fitness levels

Coaches and other practitioners

- Test players fitness in beginning of preseason (i.e. YoYo-IR2 test7); adjust the training plan when players’ fitness is lower than expected;

- Monitor response to training with simple questionnaires or ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), the latter being a good indicator for injury risk27.

Players

- If you feel real discomforts, communicate it with your coach and physio.

3. Prevent excessive chronic loads, especially at the start of competition.

Policymakers

- Allow more substitutions, as already is the case in most restarted professional competitions

Coaches

- Make use of the substitutions and rotate players when necessary and/or possible: an injured key player cannot score.

4. High emphasis on optimal recovery

Policymakers

- Allow players enough time to recover between matches, at least 5 days, but in the beginning of competition preferably 7 days;

- Limit the number of matchdays with less than 5 days of recovery when the above is not possible.

Players

- Sleep enough, drink enough (water), eat healthy.

By Tom Stevens, PhD | @tgastevens (19-06-2020)

References:

- Inmotio. Research shows: only 0.2 percent of all matches expose professional football players to close encounters. 2020; Available from: https://inmotio.eu/research-shows-only-0-2-percent-of-all-matches-expose-professional-football-players-to-close-encounters/

- Mohr M, Nassis GP, Brito J, Randers MB, Castagna C, Parnell D, Krustrup P. Return to elite football after the COVID-19 lockdown. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020 May 18; Online ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1768635

- Ekstrand J, Spreco A, Windt J, Khan KM. Are elite soccer teams’ preseason training sessions associated with fewer in-season injuries? A 15-year analysis from the union of European football associations (UEFA) elite club injury study. Am J Sports Med. 2020 Mar;48(3):723-729 https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546519899359

- Ekstrand J, Spreco A, Davison M. Br J Sports Med. Elite football teams that do not have a winter break Lose on average 303 player-days more per season to injuries than those teams that do: a comparison among 35 professional European teams. 2019 Oct;53(19):1231-123 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099506

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part II: long term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med. 2000;30(3):145-54 https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200030030-00001

- Stokes KA, Jones B, Bennett M, Close GL, Gill N, Hull JH. Returning to play after prolonged training restrictions in professional collision sports. Int J Sports Med. 2020 May 29; Online ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1180-3692

- Krustrup P, Mohr M, Nybo L, Jensen JM, Nielsen JJ, Bangsbo J. The Yo-Yo IR2 test: Physiological response, reliability, and application to elite soccer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(9):1666–1673 https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000227538.20799.08

- Askling C, Karlsson J, Thorstensson A. hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003; Aug;13(4):244-50. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00312.x

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Detraining loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part I: short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med. 2000;30(2):79-87 https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200030020-00002.

- McMaster DT, Gill N, Cronin J, McGuigan M. The development, retention and decay rates of strength and power in elite rugby union, rugby league and American football. Sports Med 2013; 43: 367–384 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0031-3

- Australian Institute of Sport. Prescription of training load in relation to loading and unloading phases of training. Bruce, ACT, Australia, Australian Sports Commission. 2020; 2nd Ed. Available from: https://ais.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/734835/Considerations-of-training-load.pdf

- Stevens TGA, de Ruiter, JC, Twisk JWR, Savelsbergh GJP, Beek, PJ. Quantification of in-season training load relative to match load in professional Dutch Eredivisie football players. Sci Med Footb. 2017;1(2):117-125 https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2017.1282163

- Martin-Garcia M, Gómez Día, AG, Bradley PS, Morera F, Casamichana D. Quantification of a professional football team’s external load using a microcycle structure. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(12):3511-3518 https://doi/org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002816

- Dalen T, Sandmæl S, Stevens TGA, Hjelde GH, Kjøsnes TN, Wisløff U. Differences between acceleration and high intensity activities in small-sided games and peak periods of official matches in elite soccer players. J Strength Cond. Res. 2019 Feb 6; Online ahead of print https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003081

- Jamil M, McErlain-Naylor SA, Beato M. Investigating the impact of the mid-season winter break on technical performance levels across European football – Does a break in play affect team momentum?, Int J Perf Anal Sport. 2020;20:3:406-419 https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2020.1753980

- Drew MK, Finch CF, The relationship between training load and injury, illness and soreness: a systematic and literature review. Sports Med. 2016 Jun;46(6):861-83 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0459-8

- Nédélec M, McCall A, Carling C, Legall F, Berthoin S, Dupont G.. Recovery in soccer: part I – post-match fatigue and time course of recovery. Sports Med. 2012;42:997–1015 http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/11635270-000000000-00000

- Nédélec M, McCall A, Carling C, Legall F, Berthoin S, Dupont G. The influence of soccer playing actions on the recovery kinetics after a soccer match. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:1517–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000293

- Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J, Hagglund M. Muscle injury rates in professional football increase with fixture congestion: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:743–7 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092383

- Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J, Waldén M, Hägglund M. Muscle injury rate in professional football is higher in matches played within 5 days since the previous match: A 14-year prospective study with more than 130 000 match observations. Br J Sports Medicine. 2018;52(17):11160–11122 https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097399

- Carling C, Gregson W, McCall A, Moreira A, Wong DP, Bradley PS. Match running performance during fixture congestion in elite soccer: Research Issues and Future Directions. Sports Med. 2015; 45(5):605-13. https://doi.org10.1007/s40279-015-0313-z

- Trackademic. The Bundesliga Blueprint: the snapshot becomes a story. 2020, Jun 17; Retrieved from: https://www.trackademicblog.com/blog/thesnapshotbecomesastory

- Bates S. Raymond Verheijen fires injury warning to Premier League clubs ahead of restart. Mirror. 2020, Jun 7; Available from: https://www.mirror.co.uk/sport/football/news/raymond-verheijen-fires-injury-warning-22150671

- FIFPRO. At the limit: Player workload in elite professional men’s football. 2019; Available from: https://www.fifpro.org/media/bffctrd1/at-the-limit.pdf

- Seward J. Bundesliga chief Christian Seifert admits ‘tens of thousands of job are at stake’ as German football is shut down in wake of coronavirus crisis. Daily Mail. 2020, Mar 17; Available from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-8121033/Bundesliga-chief-Seifert-admits-thousands-jobs-stake-coronavirus-shuts-football.html

- Toohey LA, Drew MK, Cook JL, Finch CF, Gaida JE. Is subsequent lower limb injury associated with previous injury? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51(23):1670-78 https://doi/org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097500

- Eckhard, TG, Padua DA, Hearn, DW, Pexa BS, Frank BS. The relationship between training load and injury in athletes: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2018 Aug;48(8):1929-1961 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0951-z